The French surgeon Auguste Nélaton is one of those figures better known for the company he kept than for what he did. As well as acting as personal physician to Napoleon III, Nélaton famously treated Giuseppe Garibaldi, the unifier of Italy, for a bullet wound.

It seems unfair that Nélaton is principally remembered for his connections with other people, because he was one of the greatest surgeons in nineteenth-century France. A superb operator, anatomist and teacher, he also gave his name to two surgical instruments, a syndrome, a tumour and an ulcer.

Here is one of Nélaton’s most unusual cases, which took place in 1853 at the Hôpital St. Louis in Paris. The story first appeared in several French journals, and was translated into English by the West Country surgeon Robert Brudenell Carter, a colourful figure about whom I have written before.

A man, 26 years old, applied at Nélaton’s hospital on account of a lachrymal fistula, and stated that three years previously he had received a blow, in the inner angle of his left eye, from the ivory handle of an umbrella, and that it had rendered him unconscious for several hours.

A lachrymal fistula is an abnormal opening of the tear duct, usually visible as a small hole in the skin between the eye and the nose. Some are congenital, but others may be the result of an abscess.

At that time he was taken to Desmarres’ hospital with a bleeding wound, a centimetre and a half in length, at the place of injury. This wound was examined with a probe, and it was believed that a splinter from the superior maxillary bone had been driven between the eye and the inner wall of the orbit.

The doctors believed that the impact had driven a small shard of bone from the patient’s upper jaw into his eye socket – although it proved impossible to extract:

Various fruitless endeavours were made to remove this supposed splinter, and some small white particles were brought away by the forceps. The globe was unhurt, but its movements towards the nose were impeded, and mydriasis was produced.

Mydriasis is a persistent dilation of the pupil, often caused by injury to the nerves or muscles of the eye.

The suppuration gradually diminished, and the skin contracted and healed, leaving only a fistulous opening to a channel leading to the supposed splinter. Further treatment was then abandoned, and the patient was discharged.

Sensible enough: better to be cautious rather than risk doing the patient any further damage. The young man was not badly affected by the injury, but his vision was slightly impaired. He struggled to sleep at night because lying down caused severe pain in the left side of his head. He also developed a squint, the left eye started to protrude from its socket, and the sclera – the white part of the eye – took on an unnatural yellowish tint. So, three years after the original injury, he went to a different hospital, this time to see Dr Auguste Nélaton.

Below the inner angle of the eye was a sinus, one centimetre in depth, having an external opening precisely like that of a lachrymal fistula; but the lachrymal sac was healthy, and the tears passed into the nose without impediment.

‘Sinus’ is effectively another word for ‘fistula’, i.e. an abnormal opening. Nélaton quickly decided that this was not a lachrymal fistula but a wound.

A probe, introduced with some difficulty, struck upon a very hard, smooth, and immovable substance. Notwithstanding the certainty of the patient that there was no foreign body, and his assertion that the umbrella had not been broken by the blow, Nélaton did not feel satisfied upon the point, and he determined to remove the hard substance, whatever it might be.

The surgeon made a two-centimetre incision near the corner of the patient’s eye, and delicately inserted a probe. He found that the object inside the opening wobbled slightly when he touched it.

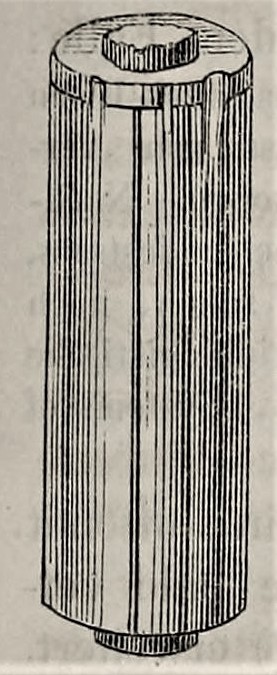

The substance was then seized with strong forceps, and, to the astonishment of everybody, an ivory handle was withdrawn, cylindrical in shape, four centimetres (one inch and five-eighths) in length, and a centimetre and a half in thickness.

Walter F. Atlee, an American who studied medicine in Paris, attended a lecture at which Nélaton described this dramatic moment. According to Atlee, the students responded to the appearance of the umbrella handle with cries of ‘Magnifique! Delicieux!’

The end that had been turned outwards showed where it had been broken from the wood of the umbrella-handle, and presented indentations, produced by the attempts at extraction made by Desmarres three years before.

The original journal article was accompanied by an illustration of the surprisingly large piece of umbrella handle:

Dr Desmarres had apparently attempted to remove this object twice: the first occasion was six months after the accident, and the second a year after that.

There followed some bleeding from the right nostril, the pains disappeared, and the eye regained its movements inwards. After a few days the patient left the hospital with his vision improved, and with the fistula nearly healed.

An umbrella handle is certainly an unexpected object to find inside an eye socket. But that’s not even the most unusual aspect of the story. Right up until the moment it was extracted, the patient was adamant that there couldn’t possibly be a foreign body there. He said that he had been shown the umbrella with which he had been hit, and its handle was intact. In his notes of the lecture in which the surgeon talked about this case, Walter F. Atlee observes that it must have been a different umbrella. Atlee also relates:

M. Nélaton spoke of the case as an example of the persistence the surgeon must have in interrogating a patient. He had multiplied his questions in every way, in order to have most positive information about this case; the shape of the handle he had seen after the blow, whether there had been a plate with a name upon it, &c. &c. He had done so, because he could not help supposing that a foreign body was there; it was with much difficulty that he had brought himself to renounce that supposition.

A useful clinical lesson for M. Nélaton’s students: listen to what the patient has to say, but trust your senses and clinical judgment more. In the world of retail the customer may always be right. But that doesn’t always go for patients.